I’m pretty sure it’s not news to anyone reading that there is a student and teacher wellbeing crisis going on.

There’s been a 162% increase in serious mental health problems in teenagers since 2019 and the problem doesn’t seem to be improving. Data collected from more than 400 teachers and almost 2,900 students during the first two terms of 2022 by a leading school wellbeing platform found that a third of all students are not coping well, which has been trending upward as the year progresses.

Given what we know about the delicacy of a young person’s formative years, and the impact a young person’s emotional health can have on everything from educational outcomes, development, and effective transition into adulthood – the school environment is a critical area of focus.

As a parent in 2022, I’ve definitely noticed that student welfare is becoming more of a concern factor for parents when selecting which schools to send their children to, than when I was a teacher in 2005 for example. Which is a good thing. But on the flipside, of course, rising parent concerns only add to the mounting pressure felt by schools and the teachers themselves.

What do we mean by wellbeing?

I’ve spoken about it before, but it is important to define what I mean when I talk about student and teacher wellbeing.

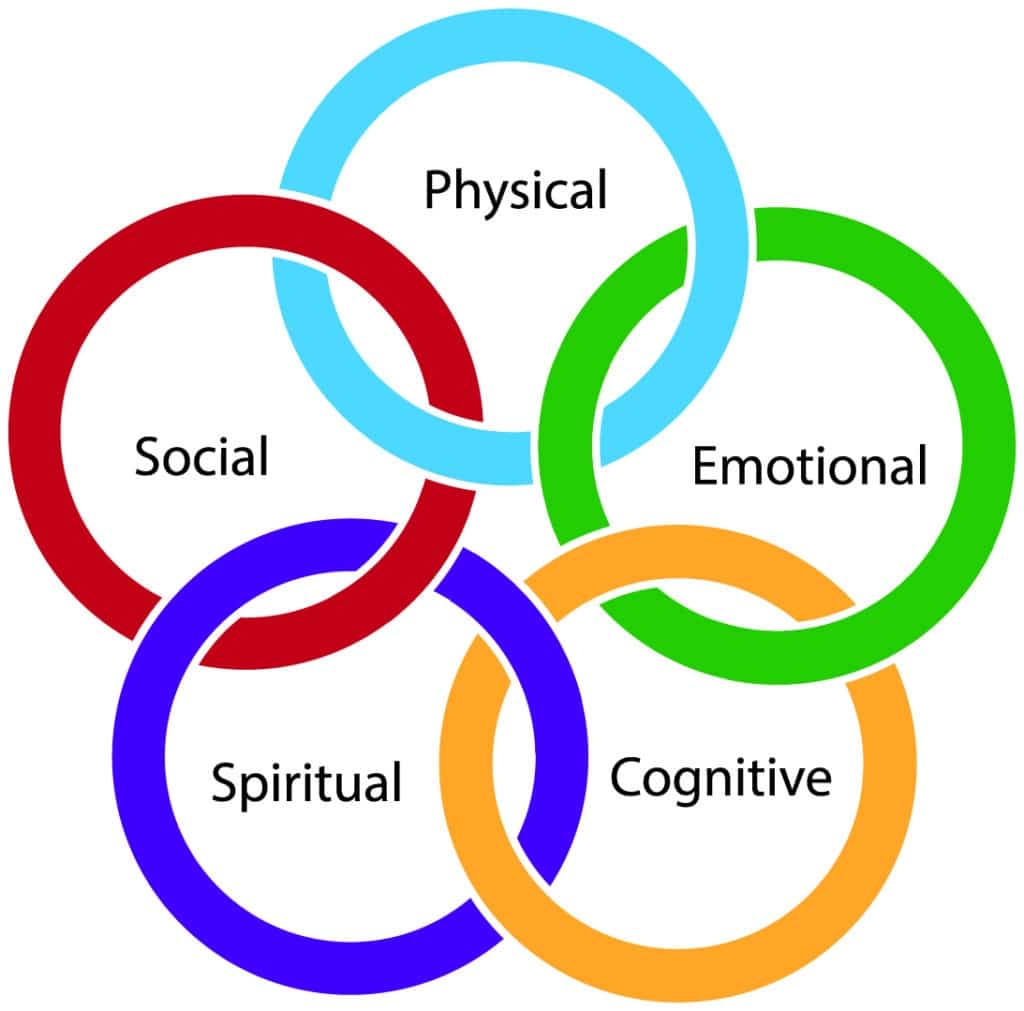

In very broad terms, it can be described as the quality of a person’s life. Wellbeing needs to be considered in relation to how we feel and function across several areas, including our cognitive, emotional, social, physical and spiritual wellbeing. And the NSW Government website reminds us that wellbeing in schools is for all. A focus on wellbeing goes beyond the welfare needs of just a few select individuals and aims for all students, teachers and the entire community to be healthy, happy, successful and productive individuals, who are active and positive contributors to the school and society in which they live.

Complexities for schools

With education being the highest household expenditure for most Australian families, how can schools answer to the rising parent demands, while reconciling the fact that the great majority of teachers are not formally trained in student wellbeing and mental health anyway?

Furthermore, given the national skills shortages impacting their workloads adding to the stress of teaching during a pandemic, teachers themselves are submitting more mental health Workcover claims than any other profession at the moment.

There are a plethora of affordable tools and self-reporting surveys out there that schools can add on top of their existing tech stacks, claiming to provide easy to use “solutions” for their student’s issues, almost like “wellbeing as a service”. But these are just the icing on the cake. Many kids with genuine problems just lie or hide the truth. Most are just in a rush to get back to their friends or phones or comfort zones, so they just select the easiest options to close the tab and submit as quickly as possible.

Schools, and the Edtech partners they work with, need to get better at scraping beneath the icing, cutting through to examine the cake cross-sectionally, and consider the broader context too.

Complexities for students

Many would argue that yet more data gathering for students is a recipe for disaster – schools are already drowning in assessments of various kinds. Aren’t more platforms, tools and apps just going to take them away from precious time out in the playground, interacting with other kids, falling over and picking themselves back up again?

Potentially yes, but the grounds for measuring pupil wellbeing – because of its links with positive educational outcomes – are simply too strong to ignore. Happier children simply learn better. They are more likely to grow into satisfied adults, build effective relationships and have less risk of developing mental health disorders. Which has implications for the rest of society, and the rest of the world too.

Data is not a dirty word

So many schools I speak with still think of ‘data collection’ as an overwhelming, 14 page, 6 tab excel spreadsheet.

The reality is that it doesn’t have to be like that anymore. The practice of routinely tracking student and staff wellbeing, even the most basic format, provides an important starting point. Even basic self-reporting can go some way to demonstrate meaningful changes and trends affecting a school’s communities week on week, month on month, year on year. And there is software today designed for the express purpose of making this reporting and data collection far easier than it used to be.

If we could shift the perception of data collection and all schools were to get on board with a simple, standardised model of routine wellbeing measurement, it may be possible to compare and contrast the data, investigating what it is that some schools do to successfully improve outcomes for their communities.

It can identify trends around certain times of year, or term, or day to day timetables – which can help inform scheduling and rostering. Anomalies may reveal risk areas or highlight vulnerabilities that can be potentially harmful or even catastrophic.

Given the impact of what is at stake – this is valuable IP that all of us in the community must be sharing.

Data is the starting point

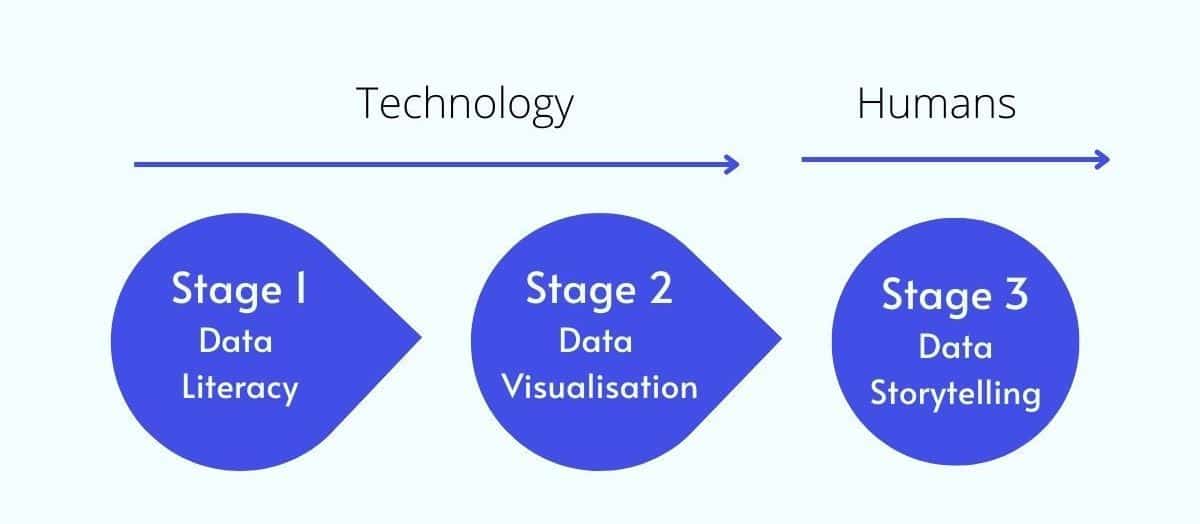

In our recent webinar with data coach and storyteller Dr Selena Fisk, she illustrated that the first two stages of a typical data journey inform the final stage – being able to tell stories with it.

I’ve added the progress indicator to show where tech can be applied to assist schools on the journey to effective data usage. But once we have a story – it should be treated just like that: a tale or supposition that may or may not be true. It’s an interpretation.

At the most basic level, knowing the unique nuances and special, unmeasurable factors affecting each individual person and each separate school, stories in the numbers can provide schools and teachers with an indicator into areas that a human will then need to dive in and investigate further.

Bringing together further behavioural and observational data alongside the stories supposed by as many tools as they can means that providers can develop a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the situation. Only then can interventions and whole-school policies be designed, chosen and tailored to suit their individual needs.

“Wellbeing as a Service”

I’m not an anxious person, but this phrase gives me anxiety. It reduces the cognitive, emotional, social, physical and spiritual health of a human being down to a metric or a KPI that is to be resolved by a tool or product of some sort, for a predetermined period of time… for a cost.

The reality is that the tools can only get us so far. Working towards better total community and society wellbeing and student wellbeing requires a holistic approach with everybody’s buy-in, taking into account multiple data points to assess the current situation, and embedding scalable, long term policies to move it forward for the better.